Presidential transitions are awkward, and Cheney had been through his share. “There’s always a certain amount of hubris involved for the new crowd coming in: ‘Well, if you guys are so smart, why did we beat you?’ And so it can get a little tense at times, but you’ve got to overcome those things, because there aren’t very many people who’ve run the White House. And there are valuable lessons to be learned. You really do want to try to equip the new guy with whatever wisdom you’ve acquired during the course of your time in office.”

Never forget the extraordinary opportunity you’ve been given to serve, and the privilege and responsibility that it represents. You are sitting next to the most powerful person in the world. Remember to value and appreciate that fact every single day you’re here.

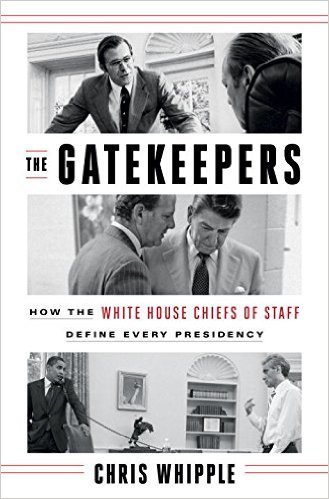

Without a great chief of staff, a president frankly doesn’t know what he is doing. One of the things I’ve learned is that the big breakthroughs are typically the result of a lot of grunt work-just a whole lot of blocking and tackling. Grunt work is what chiefs of staff do.

“All our presidents select for various positions cronies or political hangers-on or whatever. But every president knows when he’s picking his chief of staff, my God, he’d better get the right man in that job or he’ll be ruined.” Some of the great blunders of modern history have happened because a chief of staff failed to tell the president what he did not want to hear.

All might have been avoided if the chiefs of staff had put these decisions through the rigors of a system designed to avoid disasters.

People ask me if it’s like that television show The West Wing. But that doesn’t begin to capture the velocity. In an average day you would deal with Bosnia, Northern Ireland, the budget, taxation, the environment—and then you’d have lunch! And then on Friday you would say, “Thank God-only two more working days until Monday?”

Emanuel would discover just how relentless the job can be. Over the next twenty months, he would later tell me, there were no moments of peace: “You’re on the phone on the way home. You’re on the phone during dinner, you’re on the phone reading bedtime stories to your kids-and you fall asleep before the book ends. And then you’re woken up around three in the morning with something bad happening somewhere around the world.”

The executive branch of the United States is the largest corporation in the world. It has the most awesome responsibilities of any corporation in the world, the largest budget of any corporation in the world, and the largest number of employees. Yet the entire senior management structure and team have to be formed in a period of 75 days.

Having served as Dwight Eisenhower’s vice president, Nixon knew the presidency could be a “splendid misery,” as Jefferson put it, unresponsive even to the commands of the most celebrated general in modern history.

“Never bring me a sealed envelope!” Ike barked. Nothing, he decreed, should come to the president without first being screened by someone he trusted. Soon Adams was installed as the president’s gatekeeper-and the first White House chief of staff was born.

John Kennedy had rejected Ike’s model and decided he did not need a chief; he would be his own gatekeeper. A half-dozen senior aides would have direct access to the Oval Office. But then came calamity: Kennedy was gulled by the Pentagon and CIA into sending a ragtag army of anti-Castro mercenaries onto the beach at Cuba’s Bay of Pigs. They were routed, and the new president humiliated. Deceived by his generals, Kennedy concluded that he needed someone he could trust to help him with the big decisions (and to filter conflicting advice). Bobby Kennedy became his de facto chief.

But Nixon wanted someone to keep them in line, to ensure that his agenda would be executed, giving him time and space to think. H. R. Haldeman would be that person. Eisenhower had told Nixon that every president has to have his own ‘SOB.’

It turned out, somewhat to my surprise, that I was a born advance man. This is one of the most demanding jobs in politics. It needs organizational ability, a passion for predictability and punctuality, and a strong enough character to counterbalance the demands of different political groups and personalities.

And Haldeman, the consummate advance man, would take an important lesson to the White House: The president’s time is his most valuable asset.

“Our job is not to do the work of government, but to get the work out to where it belongs-out to the Departments,” Haldeman began. He continued: “Nothing goes to the president that is not completely staffed out first, for accuracy and form, for lateral coordination, checked for related material, reviewed by competent staff concerned with that area-and all that is essential for Presidential attention.”

Haldeman then warned about what he called end running: “That is the principal occupation of 98 percent of the people in the bureaucracy. Do not permit anyone to end-run you or any of the rest of us. Don’t become a source of end-running yourself, or we’ll miss you at the White House.” (End running, as Haldeman defined it, is what happens when someone with his own agenda meets privately with the president without going through the chief of staff. The result? All too often, a presidential edict that has not been thought through-with unintended consequences.)

The key staff can always communicate with and see the President when necessary. The priorities will be weighed on the basis of what visit will accomplish most. We’ve got to preserve his time for the things that matter. Now, that does not mean that everything will be reduced for him to the lowest common denominator. The President wants to make decisions himself, not preside over decisions made by the staff. How we decide what is major and what is minor is the key to whether this is a good White House staff or a lousy one.

I never intend to send another memorandum like this to the President and I don’t intend to tolerate this kind of total failure on the part of our staff ever again.

I’m not interested in any explanation, excuse, or discussion of this one, and I’m especially not interested in any more B.S. in the form of reports that tell me something has been done when in fact, it hasn’t….

Nixon saw the White House as a Fortune 500 company, with the Oval Office as the corner office, and Haldeman as chief operating officer. “Policy was going to be decided in the White House,” says Higby. “And it was the job of the cabinet to execute. And there were mechanisms put in place to make sure that follow-up and execution did take place.”

One of those mechanisms was a “tickler system.” Staffers were assigned to follow up on presidential edicts at specific intervals to be sure they were being carried out.

From the start, Gerald Ford’s White House resembled a kids’ soccer game, everyone running toward the ball. Ford had announced that he would govern with eight or nine principal advisers reporting directly to the president—a circle, with Ford at the center. He called it “the spokes of the wheel.” But the result was chaos and dysfunction.

“I told Ford that his approach-known as the spokes of the wheel, where everyone would report to him-was fine for a minority leader in the House of Representatives,” said Rums-feld. “But it would prove to be totally dysfunctional as president of the United States. It would not work. And I would not be a party to anything like it.” But Ford was adamant. First, it was the way he had run his congressional office. Second, he wanted a clean break from the tarnished image of Nixon and his imperial presidency, personified by the glowering Haldeman. The humble, plain-spoken president, a vivid contrast to the conniving Nixon, enjoyed an approval rating of 71 percent. He would run the White House his way.

The ‘spokes of the wheel’ approach wasn’t working. Without a strong decision-maker who could help me set my priorities, l’d be hounded to death by gnats and fleas. I wouldn’t have time to reflect on basic strategy or the fundamental direction of my presidency.

To keep meetings moving, he installed a standing desk in his office. Greenspan, plagued by a bad back, lay flat on the carpet. Everyone else stayed on their feet. “You could have a lot of meetings standing up that don’t last very long,” Rumsfeld explains. “Once you sit down, have a cup of coffee, let people get comfortable, then time goes. When you’re White House chief of staff, you don’t have a lot of leisure time that you can just be visiting.”

With his deputy in place, Ford’s new chief set out to execute the president’s agenda. In Rumsfeld’s view, decisions were dead on arrival unless they were translated to every relevant department. “There are very few problems in the federal government that are solely the jurisdiction of a single department,” he explains. “They almost always have legal implications, so the justice system has to be involved. They almost always have congressional implications, so that part has to be connected. They almost always are blurred between defense and intelligence and diplomacy, so that has to be done.

“Well, who does all of that connecting? It has to be the chief of staff.”

You’ve got other people who see the president once a week, once a month, once a year. Even though they may have been good friends before, they don’t have the ability to pick the right moment to talk to him and tell him what he does not want to hear. Because the chief of staff is with him day in and day out, he has the ability to select moments when he can look at a president and tell him something with the bark off. He is the one person besides his wife who can do that-who can look him right in the eye and say, ‘This is not right. You simply can’t go down that road. Believe me, it’s not going to work, it’s a mistake.’

Not everyone welcomed Rumsfeld’s ironfisted style. “There’s some hostility when you have a tough guy who is not dancing around issues and is returning a paper and saying, ‘This is not presidential, this is not ready for the big leagues,’ “ says Terry O’Donnell. “But Rumsfeld was firm and did not mince words. That was what Ford needed and he delivered it.”

The vice president was about to get a master class in bureaucratic infighting from the chief of staff.

“President Ford would say, ‘Gee, Nelson, why don’t you come in with some ideas on energy?’ “ recalls Rumsfeld. “And Rockefeller would take a group of people, fashion a major program, take it to the president, and expect him to send it up to the Hill. So the president would say to me, ‘Well, what should I do with it?’ And I said, You have to staff it out: give it to the Department of Energy, the Office of Management and Budget, economic advisers, secretary of the Treasury, and the like.’” Staffing out his proposals was an almost certain way to kill Rockefeller’s big-spending agenda. And sure enough, nearly all the vice president’s plans were DOA.

“The vice president got it in his mind that Henry Kissinger was in charge of foreign policy and Nelson Rockefeller was in charge of domestic policy, which means we didn’t need the president,” Rumsfeld recalls. “I can remember explaining to him that ‘heading up’ domestic policy did not mean overriding cabinet officers who had statutory responsibilities on those subjects. And in that stage of his career he didn’t take advice-or no—graciously.”

In a kind of shakedown cruise, Rumsfeld sent Cheney on a presidential trip to Mexico, where he impressed Ford with his low-key, no-drama efficiency. “I said, ‘How did he do?” “ recalls Rumsfeld. “And the president said, ‘Terrific. He comes in, has his business to talk about, talks about it, and gets out. And goes about it and takes care of the business. He’s a fine person and I’m happy to work with him, so rotate him in whenever you want.’”

“Rumsfeld did not take advice or even think about anybody else,” recalled Gail Raiman, a White House secretary. “Frankly, he was going to do X, Y, or Z, and just do it. And not in the kindest way.” By contrast, Cheney was collegial, collaborative, and considerate-the antithesis of the Darth Vader character he would become decades later as George W. Bush’s vice president. “Cheney was very different,” recalls Scowcroft. “The difference between Rumsfeld and Cheney was the difference between night and day. Cheney was very relaxed, not uptight, not overbearing. His attitude was We all have to pull together to make the presidency work.’”

Genial and self-effacing, Cheney was a good listener with a gift for defusing outsized egos; his Secret Service name was “Backseat.”

We got it down to a schedule and we got time for him to think, and do some of the things that Haldeman found so very important. Papers were organized, scheduling issues were carefully thought out before they were put on his plate. Rumsfeld and Cheney strengthened that framework, making sure that the president was well served by the staff.

There were forty or fifty initiatives that were bouncing around!” Eizenstat sensed that their agenda was spinning out of control: “It doesn’t take but about twenty-four hours in the White House for all the problems to converge— to know that you’ve got to have someone to sort through this thick-et, to try to make sense of it. What priority do you set-when you’re trying to get your energy policy done, when you’re trying to get your stimulus package passed, when you’ve got tax reform coming up at the very same time? Everything in Washington is connected. Everything. You step on their toes on one thing, they’re going to remember on the next thing.”

The former one-term governor was learning by total immersion. “I’ll never forget one time I was talking to Brzezinski about Carter,” recalls Brent Scowcroft. “And he said, ‘He’s wonderful. I can give him 150 pages to read at night-and he reads it. He makes marginal comments.’ And I said, ‘Zbig, that’s a terrible thing for you to do. Because he doesn’t have time for that.’” No detail of governing was too trivial for the president’s attention.

The president looked haggard and aged. “It’s become obvious to me,” Carter wrote in his diaries, “that we’ve had too much of my own involvement in different matters simultaneously. I need to concentrate on energy and fight for passage of an acceptable plan.” But instead of focusing, Carter’s response was to work harder across the board. “We probably had two hundred people and all of them horses, all of ‘em passionate, all of ‘em hardworking,” says Butler. “So somebody had to set an agenda. Somebody had to set the tone and say, this is important, and this isn’t. And that wasn’t easy to do.”

“Every president looks fifty years older when leaving office,” says Fallows, “be-cause even somebody who figures out how to win the office can’t really imagine the demands it brings and the complexity. And so it’s difficult to have the tragic imagination of how hard it’s going to be-especially if, like Carter, he had had a high estimate of his own abilities.”

Fallows pauses, as he considers Carter’s successor. “And maybe that’s the strength of presidents like Reagan-who don’t think they’re the smartest person around.”

Carter and Reagan were opposites: the former a compulsive micromanager, the latter a gifted performer trained at hitting marks set by others. “Not because Reagan didn’t have any skills or anything, but I watched him as governor,” says Spencer. “Reagan was, ‘I’ve got a role to play, I’ve got a script to learn-and you’re a producer, you’re a director, and you’re a cameraman: Now you do your job and I’m gonna do mine.’”

Carter was arguably the most intelligent president of the twentieth century, whereas Reagan had once been called, unfairly, “an amiable dunce.” Yet in choosing Baker, Reagan had intuited something his predecessor did not grasp. As kea-gan’s biographer Lou Cannon wrote: “He did not know one missile system from another and could not explain the simplest procedures of the federal govern-ment, but he understood that the political process of his presidency would be closely linked to his acceptance in Washington. In this he was the opposite of Jimmy Carter, who knew far more and understood far less.”

Orderly schedule & orderly paper flow is way you protect the Pres.

Well designed system. Got to be brutal in scheduling decisions.

Most valuable asset in D.C. is time of RR

Need to have discipline & order & be discriminating

“One thing I believed was to surround yourself with really good people,” he says. “A lot of people were afraid to do that for fear it would take the sheen off them.” At fifty, Baker had nothing to prove. “I’ll tell you this,” says Margaret Tutwiler, “and I believe it about Baker and I believe it about Reagan: The most successful managers are those that are secure enough to surround themselves with extremely strong-willed, talented people.”

Baker charmed the jaded press corps by telling them everything he could on “background”; he warned them off half-baked stories and was always accessible, day or night. (Though he rarely agreed to be quoted directly.) “He understood that the press corps was part and parcel of governing,” says Tutwiler. “He always treated them with respect-even if he couldn’t stand the individual he was dealing with.”

Не had this zen quality. He was put together and he just exuded this air of calm and cool and above it all. He was the one with the secret sauce. He was the one who you thought knew everything; he was giving context and perspective-without spin; whether you agree or disagree, you know he was a straight shooter. That’s what everybody felt. He was a straight shooter. And extremely bright.

In the gospel according to Baker, preparation was the first commandment. “Day in and day out, he’s focused. He does not wing it. He thinks before he speaks,” says Tutwiler of the man she called Mr. Cautious. “He has that yellow legal pad, and he writes everything down.” Baker logged sixteen-hour days and personally returned every phone call, no matter the hour. “I’m driving down Pennsylvania Avenue one night with Reagan,” says Stu Spencer. “And all the lights were on in the West Wing. And Reagan says, What’s with all the lights on?’ I say, ‘Well, they’re working.’ And he goes, ‘Oh my God, tell Baker to go home?”

“Baker is not perfect,” says Tutwiler. “But he can handle pressure. He’s a Steady Eddie. And he’s a realist. It’s almost clinical. He doesn’t lead with emotion. He can handle a whole lot of incoming and just not get rattled.” Baker’s version is that he simply delivered a dose of reality.

“Baker delivers bad news in a most respectful way,” says Tutwiler. “It’s not that he’s sycophantic; he’s not at all-but he has a lot of patience. He has an enormous amount of personal security because he was somebody before he came here.” Spencer adds, “Jimmy was good at sayin’, ‘Hey, boss, you’re wrong.’ He learned one thing from me: You can stand up to a president who is a secure individual in his own right.”

Failing to prepare for debates is a form of hubris shared by presidents who run for a second term. “It’s not that they get rusty,” says Tutwiler. “It’s an attitude. ‘I’m president of the United States-what are you talking about? I’ve got Air Force One, I’ve got Marine One, I’ve got all this stuff. I’m not gonna put up with this.’”

“It wasn’t a fun time,” says Tutwiler. “I mean, this isn’t bean bag, as you know. I think that politics, generically speaking, is a user business. And if you want to get into it to be thanked all day long for your great contributions, you’re in the wrong business. Whether it’s Jim Baker or somebody at my level, that just doesn’t exist.”

“Presidents sometimes make the mistake of hiring for the White House chief of staff somebody who brought them to the dance, rather than the person who needs to be the dance partner once you’re governing,” he says. “In campaigning, you try to demonize your opponent. In governing, you make love to your opponent. That’s how you put coalitions together. Jim Baker understood campaigning, but he was a real pro at governing.”

Ideally, the chief is the COO to the president’s CEO. “Regan thought he was the CEO,” says Duberstein, “and Ronald Reagan was the retired chairman of the board.”

From his post at Treasury, James Baker observed Regan’s troubles with a dose of schadenfreude. “Regan said there is not going to be a sparrow that lands on the White House lawn that I don’t know about,” Baker recalls. “And then Iran-Contra broke. And there were stories in the press quoting Don Regan saying, ‘Iran what? Iran-Contra? Who me?’ “

Howard Baker was eager to demonstrate that he was no Don Regan. “You can’t be a president’s chief of staff if you think you are president consciously or unconsciously,” he said. “You’ve got to realize, as much as it bruises your ego perhaps, that you’re working for him, and carrying out his policies. You’re free to argue with him, to debate with him, to disagree with him-but you can’t ever substitute your judgment for his.” Or hers. Baker quickly learned that Nancy was also a force to be reckoned with. One day Jim Cannon ran into Baker—red-faced, flustered, and clearly shaken, having just come from a one-on-one meeting with the first lady. The new chief blurted out: “Don’t let anyone tell you that there has never been a woman president of the United States!”

For Reagan, the presidency was never, in Jefferson’s phrase, a “splendid misery.” It was instead, as Lou Cannon wrote, “the role of a lifetime.”

In his view, Sununu had two strikes against him as a would-be chief: The governor not only had been a “principal,” as Don Regan had been, but he was also an outsider to Washington. Finally, Sununu could be insufferable-sometimes wrong but never in doubt. Even Barbara had to admit, “He did not suffer what he considered ‘fools’ gladly. So I think it made John occasionally seem arrogant. But you know, people are so afraid of me too!”

Moreover, Bush had taken a pounding from the press for his supposed spinelessness. George Will dubbed him Reagan’s “lap dog,” and cartoonist Garry Trudeau eviscerated him as a political eunuch-he’d “put his manhood in a blind trust.” Even Newsweek ran a Bush cover titled “Fighting the ‘Wimp Factor?” The slights had wounded him deeply (and enraged his son George W.). Bush knew that he needed a chief of staff-but he, the president, would call the shots.

After they filed out of his office, Sununu turned to his mild-mannered deputy, Andy Card. “You know what’s going to happen now, don’t you?” he said. “They’re going to go back to their offices and tell everyone, ‘That Sununu is a tough son of a bitch!’” Card, whose wife is a minister and who rarely swears, looked at Sununu. “No, they’re not,” he replied. “They’re going to go back to their offices and tell everyone, ‘That Sununu is a fucking asshole!’”

“He is an incredibly quick study, an extremely smart guy; and one of the prerequisites for that job is to know politics and policy,” says Bates. “To be able to size up an issue quickly. He was able to do that and understood the political ramifications. Something may be a good policy but does it have a chance of passing? He had a good grasp of that. He seemed loyal to the president. I saw him go toe to toe with some greats from industry and he would defend the president vocally and adamantly and seemed to enjoy sparring with them.”

Bush was leading with his head, not his gut. “It was clear to me in discussions with the president and Brent and Jimmy that everybody was trying to work through this without a preconceived decision and come at a decision as a result of logic, not of an emotional reaction,” says Sununu.

“That was a textbook case of how you fight a war,” says Baker. “You get in, you do what you said you’re going to do, and you get out. And you have overwhelming force to get the job done.” The first Gulf War’s strategy of winning with decisive force would become known as the “Powell doctrine.” (In a bitter irony, Powell would later be remembered for his prominent part in promoting another, ill-fated American war in Iraq-one in which the forces sent would be far from decisive.)

The success of Desert Storm transformed the perception of George H. W. Bush. One poll reported his approval rating at 90 percent. But the euphoria would be fleeting. At home, a stubborn recession had taken hold. Bush realized that in a tough reelection battle, his credentials as a war hero would mean less than the state of the economy.

“Sununu just didn’t know how to play the role,” says Reagan’s old friend Stu Spencer. “He didn’t know when to come forward and when to stay in the background-like Jimmy Baker] did and Cheney did and Ken [Duberstein] did.”

It is as if his attitude were “I am so powerful that I do not have to be nice, or even minimally civil, to other people.” In this he was ignoring the old Lebanese proverb that holds, “one kisses the hand that one cannot yet bite.” When Sununu got into trouble those who previously had to kiss his hand turned to bite it.

It is with reluctance, regret and a sense of personal loss that I accept your resignation as Chief of Staff…John, I find it difficult to write this letter both for professional and personal reasons.

I hope you and Nancy, free of the enormous pressures of the office you have served so well, will enjoy life to its fullest. You deserve the best.

Most sincerely from this grateful President,

“In searching for enemies who would have liked to do in John Sununu if they had the chance, one is reminded of the Agatha Christie novel Murder on the Orient Express…in which many suspects on the train had sufficient motive to have killed the victim. The mystery is solved when it is disclosed that each of the suspects was guilty because each had plunged the same knife into the victim.”

Bush believed that politics and governing should be separate, like church and state; he wanted different people in charge of the White House and the campaign.

“It was a mess. I mean, really a total mess,” he says, shaking his head. “People would wander in and out of the Oval Office, the president would get a little bit of information here, a little bit of information there. And so it took him more time to make worse decisions.”

“The fact that on the campaign trail he would linger with people, listen to them attentively, remember what they said-the great empathy, I-feel-your-pain-was absolutely true. But in trying to manage the White House, stay on schedule, move things forward, it may not serve quite so well.”

But the problem wasn’t just Clinton. “Every fifteen minutes of every day was scheduled,” says Bowles. “The president had this reputation for being late. Of course he’s late! He lives in a changing world, and if you have every fifteen minutes of every day scheduled, he’s gonna be late! So to me that was poor staff work as opposed to the president’s fault.”

Jovial and collegial, Panetta had a humble manner. But few mistook his gregariousness for weakness. There would be no more uninvited guests dropping in on the Oval Office. “Leon has an iron fist in a velvet glove,” says Reich. “He’s not a disciplinarian for the sake of being a disciplinarian; he’s actually a very gentle soul, but he knows when discipline is necessary.”

Bowles, who got his share of midnight calls, says they were Clinton’s way of thinking out loud. “With President Clinton those calls didn’t always require an answer. What he was doing was thinking through a problem and he wanted somebody he trusted who wouldn’t go blab about it. Just listen.”

“Working for Bill Clinton is a very special experience because you’re dealing with somebody who’s extremely bright, who’s got a mind like a steel trap, gathers all the facts, doesn’t forget a thing, and at the same time wants to be able to get input from everybody. And then when he makes a deci-sion, his mind doesn’t stop. It keeps churning. He keeps working it, and the toughest part of dealing with him was to say, ‘You’ve made a decision. Now we’ve got to move on. We’ve got other decisions to make.’”

“I told him, ‘Hell no, I wasn’t going to fire him,’” he says. “The president would say, ‘Why not?’ And I’d say, ‘Because every time you come out of that Oval Office and you’ve got some new thing you want us to do, and I can’t get the bureaucracy to do it, you know what I do? I give it to Rahm. And two days later he comes back and it’s done! There are twenty dead people back there-but it’s done!’”

“Rahm is a doer, and he gets it done come hell or high water, and sometimes he steps on a lot of people to get it done. But he’s gonna take the hill. And that’s a good quality,” says Panetta, “but the best way to deal with that is to make sure that you keep your arms around him, so that he doesn’t just feel that he can do anything he wants on his own.”

While he kept aides on a short leash, Panetta knew how to motivate his troops. “Leon is not a bully,” says Reich. “He’s not an attack dog. He’s really a very sweet man. What Leon proves is you don’t have to be a bully or an attack dog to be an effective chief of staff. You just have to be very smart. You have to know when to be tough, and also when to let the reins be a little looser. Because the people around you have to have some degree of autonomy or else they’re not going to do well.”

“What I could not tolerate as chief of staff was to have somebody who was planting political advice with the president and then trying to implement it through the staff of the White House,” he says. “That’s where I drew the line and told the president, ‘Look, this is unacceptable. I can’t have any political person trying to deal with the staff. And the president to his credit respected that, and we told Morris that he’s got to present the information to the president and to me, and then we’ll decide what does or does not get done. Morris understood that he was going to have to play by my rules.”

The entrepreneur-investment banker defined the job in corporate terms. “I always thought of the president as the CEO,” he says. “He’s the one that sets the agenda. It’s his presidency, not yours. And the job of the chief of staff is to be the chief operating officer-to make sure that if he sets the goals, you set the objectives, the timelines, and the accountability to make sure that what he wants done is done, when he wants it done, and is done right.”

“As Don Rumsfeld told me, ‘You’ve got to be prepared to be fired,’” Bowles says. “‘Because if you’re not, then you’re not going to give him the right advice. And the right advice is not always yes.’”

“The power of the chief of staff is derived,” says Bowles. “If you have the trust and the confidence of the president, you have all the power you need to get what you need done. If you’ve lost the confidence of a president, people smell it, feel it, know it within seconds—and you become an overblown scheduler.”

“I broke the job down into the care and feeding of the president; policy formulation; and marketing and selling,” recalls Card. “You have to make sure that the president is never hungry, angry, lonely, or tired, and that they’re well prepared to make decisions that they never thought they’d have to make. You have to manage the policy process and make sure no one is gaming the president. And the last category is marketing and selling. If the president makes a decision and nobody knows about it, did the president make a decision?”

Cheney was unapologetic. On Meet the Press, the vice president told Tim Russert that the United States would have to go to “the dark side” if it wanted to best al-Qaeda. “I said, We’ve got to spend time in the shadows in the intelligence world. A lot of what needs to be done here will have to be done quietly, without any discussion, using sources and methods that are available to our intelligence agencies.’”

“But after 9/11 he just really turned. I think something really, really happened to Dick Cheney. A good guy before, low-key, made things work, but not in a big pompous way—and then he just went way, way…” Scowcroft’s voice trails off.

Bush had never been comfortable with his celebrated general and diplomat; to him, Powell was like the popular, know-it-all older brother who was always telling you what to do.

I told the president I thought his apparatus was not serving him as well as it should, because he wasn’t being given alternatives. I rarely intervened in national security meetings, but I viewed it as my job as chief of staff to be the one to say, Why aren’t you giving the president better options? Why aren’t you letting him decide, other than having to go along with the military strategy as it’s presented to him? The president was elected to make these decisions.’

The most gut-wrenching decision was in September of 2008, when the economic advisers came into the Roosevelt Room and told the president that the calamity that was over the cliff was as great, and possibly greater, than the Great Depression. And the medicine they were bringing was something that would have been anathema to any Republican president, including this one-which was, ‘Go to the Congress and ask them to appropriate nearly a trillion dollars, to hand out to the Wall Street fat cats and banks that caused the problem in the first place.’

The son’s war, Operation Iraqi Freedom, cost the lives of 4,491 Americans and hundreds of thousands of Iraqis; it left approximately 32,000 Americans wounded.

Brent Scowcroft believes the true motivations had little to do with WMDs. “After 9/11, I think they said, ‘Look, this is a nasty world, we’re the only superpower and while we’ve got that unprecedented power, we ought to use it to remake the world. And we’re in this mess. Why don’t we take this little jerk of a dictator, kick him out, make Iraq a democracy, it’ll spread to the region, and we will have done something for the world.’” Colin Powell offers a view remarkably similar to Scowcroft’s. “They had this thinking—I’ll call it that, nothing more— that if only we could make a democracy out of Iraq, the whole Middle East would change. I have no idea how they came to that conclusion.”

Next Panetta weighed in. “I said, ‘Mr. President, you’ve got to have a chief of staff who can be your son of a bitch when tough decisions need to be made,’” he recalls. “‘You’ve got to be the good guy. That person has to take the heat for it. And that should not be one of your pals-who might share the same concern that you have about getting rid of somebody.’”

But Emanuel’s upbringing had taught him that “when the president asks you to do something, you had two answers which are yes or yes sir. And I kept, for about twenty-four to forty-eight hours, trying to figure out if there was a ‘none of the above’ answer. And I knew there wasn’t.”

Rahm really believed that a crisis is a terrible thing to waste, which was one of his famous lines early on.

“You have to remember that the Obama world was conceived in opposition to the way things had been done in Washington,” says a former White House staffer who worked on the campaign. “And that is not just the Republicans, but Democrats-specifically the Clintons. So the idea of overreacting to the news cycle, the idea of tough, hard-charging politics, Obama ran against a lot of that.” As for Emanuel: “Rahm had a very Washington view of us: ‘Yeah, they got this far. Hope and change and all that kind of stuff. But they’re all young, they’re all naive. There’s too many kids running around—and we’ve got to be a little more serious.’”

Bowles, Emanuel’s old boss in the Clinton White House, chalks up some of his legendary bluster to insecurity: “Rahm’s a pussycat underneath it—he gets his feelings hurt like poof.” Bowles snaps his fingers. “If Obama didn’t go to his fiftieth birthday party, it’d kill him.”

Emanuel thought a veto would poison relations with Capitol Hill. “It’s messy, but Rahm was like, we just have to get it done,” recalls a senior official. Obama hated the bill, but ultimately saw it Rahm’s way and agreed to sign it. “And the campaign people were aghast, because this was a guy who had campaigned on this purity and no earmarks and blah, blah, blah. And the first thing, literally, he does, is sign a bunch of messy appropriations bills.

But Obama was unmoved. What was his political capital for, if not passing the most important part of his domestic agenda? “I didn’t come here to put my popularity up on a shelf and admire it,” the president said. And then he told them, “Come on, isn’t anybody else feeling lucky? I’m feeling lucky.” Emanuel got the message. “The president made his call, he went with health care first.

“The rewards are few,” he says of being chief of staff. “The pains are mag-nified. You get all the blame and never any of the credit. You are in the cockpit seat. And when anybody gives you advice about, ‘Oh, you should do this. You should do that’-unless they’ve sat in that cockpit seat and been strafed by friendly fire as well as enemy fire, they don’t know anything about the job. Is it miserable going through it? Are you getting wind shear, whiplash, can’t tell vertical from horizontal-up from down?”

Women are always considered to be bitches when they’re tough and strong; men are considered to be powerful and heroic.

In all things, but especially foreign affairs, he is a fanatical believer in process. It stems in no small part from his belief that lack of process led the United States into Iraq. “When I sat with the president to talk about the job, I told him, ‘If you’re looking for a domestic policy adviser like Jack or like Rahm, I’m not your guy,’” says McDonough. “‘If you’re looking for someone who will get you something square, honestly arrived at, transparently developed, then I’m your guy.’ So the way I see it, I’m a keeper of a process that gets things to the president.”

“The most important thing a chief can do, and I learned this from Jim Baker’s book,” he says, “is establish clear lines of responsibility. As a result, you get clear accountability. There’s no accountability without clear responsibility.”

As smart as Obama is, he doesn’t like politics, he doesn’t like the give-and-take that it takes to get things done.